James John Messer

- Ann Ball

- Sep 4, 2024

- 9 min read

James John Messer’s Early life:

James John MESSER was my husband’s 3X great-grandfather. He was born in late 1805 and was baptised on 12 January 1806 in “St George-in-the-East” parish church in London. The church is in Shadwell, about 20 minutes’ walk east of Tower Bridge.

His parents were James John Messer (senior) and Darcy Messer (formerly BIRD). James John senior was a cordwainer, so someone who made new shoes. James John was the eldest (I think) of their children. They seemed to have trouble thinking of new names for their children because they were called:

James John b 1805 | William George b 1814 | Elizabeth Frances b 1822 |

Ann Mary b 1808 | George William b 1816 | Catherine Alice b 1825 |

Mary Ann b 1809 | Frances Elizabeth b 1818 | Thomas George b 1827 |

John James b 1812 | Richard b 1820 | Robert Walter b 1831 |

The family lived in Philip Street and were reasonably well off.

The Charles Booth Poverty Maps were created between 1898 and 1899 and were part of the data collected for the Inquiry into Life and Labour in London (1886-1903). Researchers visited every street in London and recorded what type of people lived in each street (indicated by the different colours on the maps) . Phillip Street was shaded pink (the middle of the seven colours). The maps are more recent than the time we are looking at but do show what London looked like before the bombing of World War II changed a lot of London. Very few of the streets I mention in this document still exist. There are more Booth maps later in this document.

The next thing I know about James John is when he married Louisa Harriett KEENE on 2 October 1830 in St Marylebone:

It is hard to read but is says that they were both “of this parish”, and the witnesses were Eleanor and William Keene – probably Louisa’s father or brother and her sister. What is interesting is that they all signed their own names, which means that all four of them were educated – in 1830 quite an achievement. St Marylebone is the area between Oxford Street and Regent Street, a much nicer part of London than St Georges in the East.

The “old-fashioned” marriage certificate doesn’t give James John’s occupation but his children’s baptisms entries and the next couple of censuses do:

I know he worked at the Marylebone Workhouse for all of that time, as shown in an article you’ll see below. I’ve got no idea why he called himself a gentleman sometimes – this usually implied the person was rich enough not to work. I don’t think that was the case here. The family lived in St Johns Wood for the next 20 years or so, near to Lords Cricket ground and not too far from his workplace.

2. Workhouses and workhouse occupations

What is a workhouse?

In the 1800s there weren’t any government benefits in Britain and Ireland. The “relief” was provided by the Church parishes. Wealthy people in the parish, called ratepayers, paid a rate to the parish and this was used to help people who couldn’t work. There were two types of relief – indoor and outdoor. Indoor relief was for able-bodied people and was in a workhouse. Most assistance was granted through a form of poor relief known as outdoor relief – money, food, or other necessities given to those living in their own homes.

In 1834 Poor Law authorities took over from parishes but they were still funded by the ratepayers. Workhouses were not nice places. They were designed to be uninviting, so that anyone capable of coping outside them would choose not to be in one. Some Poor Law authorities tried to run workhouses at a profit by making their inmates work for free but others paid inmates. Common jobs were breaking stones, crushing bones to produce fertiliser, or using a large metal nail known as a spike to undo old, tarred, rope. People claiming outdoor relief had to pass strict tests. If they passed the tests, they were given food or money for accommodation – but not much. For most of his career at Marylebone workhouse James John was providing outdoor relief.

At the end of 1846, pressure on the main St Marylebone workhouse was at an all-time high, fuelled to a large part by the famine in Ireland and a change in the rules that meant someone could claim relief if they had lived in Marylebone for 5 years. St Marylebone had a considerable Irish community who could now claim relief without fear of repatriation to their home parish (or Ireland in the case of Irish people).

As numbers rose, so did the cost of providing for them, and severe measures were introduced, including cuts to how much inmates were paid who were employed in the Marylebone workhouse. Nurses and laundrywomen received 1 shilling (£4) per week, the inmates who taught handwriting in the girls’ school received 1s. 6d (£6), and the cook and the barber received 2s. (£8). The reductions saved £500 (£40,100). The values in brackets are the current value. A proposal to abolish the inmates’ Christmas pudding was rejected, although portions were limited to 8oz (200g) and raisins substituted for currants. In early 1853 there was an inquiry into the poor conditions at the workhouse. I don’t know if anything improved.

Relevant Workhouse Occupations

Board of guardians – a committee of people who ran the workhouse, usually wealthy people who might also have supplied goods to the workhouse.

Clerk or Secretary – organised meetings and took minutes.

Relieving Officer – evaluated the cases of all persons applying for medical or poor relief; authorised emergency relief or entry to the workhouse. Often had an assistant.

Overseer – administered collection of local poor-rates.

From the baptisms above we can see that James John did most of these jobs at different times. From newspaper articles I have worked out that most of the time he was an Assistant Relieving Officer, responsible for giving people benefit to keep them out of the workhouse. He also acted as Secretary to the Board sometimes. He often appeared in court representing the workhouse as a witness.

Marylebone Workhouse was on the Marylebone Road, opposite where Madame Tussauds is now. James John and his family lived in Cockrance Street (now Cochrane Street). 3.

3. A bad decision

Early in 1854 James John made a bad error of judgement – he attended a meeting of the Board of Guardians “in a state of intoxication”. The Board decided to sack him. The article below from the Morning Advertiser newspaper of 11 February 1854 gives more detail. His explanation was that he had been taking a patient to Peckham Lunatic asylum and on the way back he met a friend and they went to taste wine etc in the London Docks (a pub) and it got the better of him. I think his actual mistake was going to the meeting in a drunken state!

A week later another article appeared where some board members and ratepayers stood up for James John and asked for his dismissal to be reviewed. Someone proposed that the Board should “at least grant an inquiry to his conduct rather than at once consign him and his family to utter ruin after 23 years’ service”. They also pointed out that “Mr Messer was a most efficient officer, as shown by the fact that he had on average 300 cases to legislate upon weekly”.

From another newspaper article I found a description that said he worked from 8am to 5pm six days a week so he was deciding whether 50 people a day got a benefit as well as doing other types of work

4. What James John did after leaving St Marylebone workhouse

What happens to the family for the next 15 years or so is hard to work out. James John needed to find work to save his family from “utter ruin”. I’ve found articles in newspapers that fill in some of the gaps.

A brush with the law In March

1856 articles similar to the one to below from Morning Post 21 March 1856 appeared in many newspapers around the country.

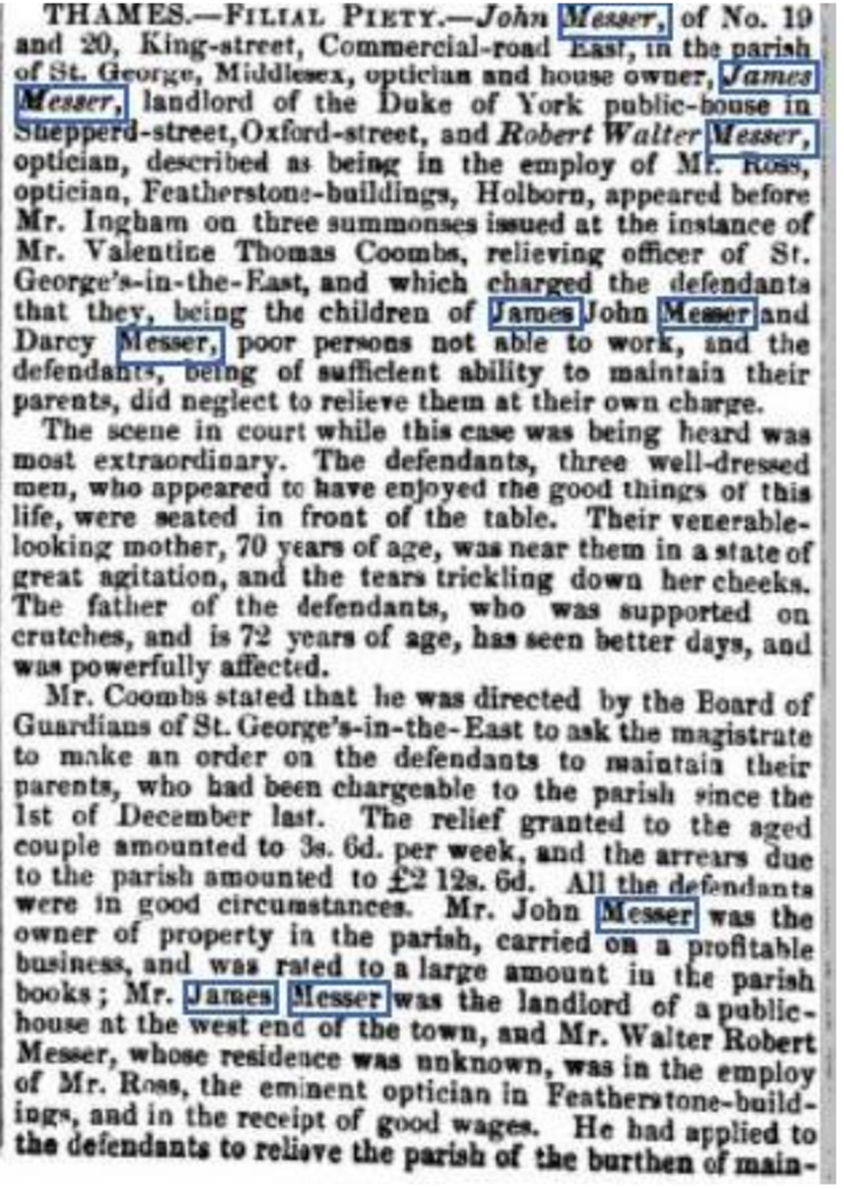

James John Messer senior and his wife Darcy (now aged between 72 and 70 respectively) had applied for relief from their local workhouse, St George-in-the-East. The workhouse, trying to find someone else who could look after them, took the brothers, James John Messer, John James Messer and Robert Walter Messer, to court. The workhouse felt they should be providing for their parents. For a long time I didn’t think it was the same James John Messer – but the other names in the cases prove that it is.

So, in 1856 James John was the landlord of the Duke of York pub in Shephard St, just south of Oxford Street.

In 2015 my husband and I and I visited this pub. The name of the street has changed to Dering Street, and it is between Oxford street and New Bond Street. Unfortunately, inside had been changed a lot and no one could help us with its history.

1861 Census

The next mention I can find of the family is in the 1861 Census. They had moved to 37 Wenlock Street in Hoxton. Louisa Harriett (James John’s wife) said she was the head of the household and she was living there with Louisa Elizabeth, William Henry, Thomas Henry (my husband’s 2X great-grandfather), Robert Rouse, and John Gilchrist. Some of the older children had married and moved away. James Bowden was a plumber and still living in Marylebone, Mary Ann was living with her family in Ecclesall Bierlow in Yorkshire (just south of Sheffield), and George Thomas was living with his family in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk. Interestingly, James John wasn’t at home – he was in Norwich, Norfolk, staying in a pub. I wonder if he was on his way to or back from visiting George Thomas? We’ll never know.

Wenlock Street was very close to St Lukes Workhouse, Hoxton and I’ve found newspaper articles that mention “Mr Messer of St Lukes Workhouse” giving evidence in a trial in 1868. This could be James John but it could also be his son, William Henry. I can’t work out which.

Moving to Deptford

In the 1871 census James John and family had moved to 10 Dock Street, Deptford. His occupation was as a licensed victualler – he was running a pub. Deptford is south of the River Thames.

I had trouble working out where this pub was because it had two names at different times. But when James John was there it was called “The Royal Marine”.

He died on 4 November 1873 at the Royal Marine. The cause of death was given as Chronic Bronchitis and heart disease.

I think the John James Messer who registered the death was his son. This is the son (b 1850) whose name changed from John Gilchrist to John James. At this point he is a law clerk and he later became a solicitor.

5. The pub in Dock Street, Deptford

The pub that James John ran was in a rough area of London. The pub is where the pink square is and means “some comfortable, some poor”. The blue area next to it means that that street was classed as “very poor, some chronic want”.

Finding the pub in records has been hard because it keeps changing its name, and the address and name of the street keep changing. Eileen and Charlie Gallagher, who were the publicans when we visited in 2015 helped sort it out for me.

The original name for the Royal Marine was the Dog & Bell, Dock Street, and from possibly as early as 1749, although the earliest recorded instance is in 1814 at the Old Bailey. It is referred to in a sea shanty - 'Homeward Bound' which was printed in 1849 and sold until 1862. The words of the sea shanty are:

HOMEWARD BOUND (From Oxford Book of Sea Songs, Palmer)

Trade directory entries list the pub as the Dog & Bell until at least 1856. The renaming of the pub to the Royal Marine was by the then publican intent on capturing the "more respectable Marines" who were lodged in Deptford Dockyard as opposed to the more local ne'er do wells!!

This was before James John and Louisa Harriett took over. After he died, she ran the pub until she died in 1883. Then Thomas Henry (my husband’s 2x great-grandfather) ran the pub for a while. He was trained as a printer and left the pub in July 1891 to go back to being a printer.

The pub name was eventually changed back to Dog & Bell. Below is a photo, taken in the 1970s, of the pub – the name is Dog & Bell, but the sign is of a Royal Marine!

And below is a photo Charlie Gallagher took of me and my husband behind the bar.

Comments